The Odyssey of Consensus: From Byzantine Generals to Blockchain

How do computers agree on the truth when some of them might be lying? This deceptively simple question has driven four decades of innovation in distributed systems, culminating in the consensus protocols that now secure trillions of dollars in cryptocurrency and critical infrastructure worldwide.

The Problem: Agreement in the Face of Betrayal

Distributed systems—from cloud services to blockchains—rely on multiple independent computers (nodes) agreeing on a single source of truth. This is called consensus. But what happens when some nodes fail, or worse, act maliciously to disrupt the system?

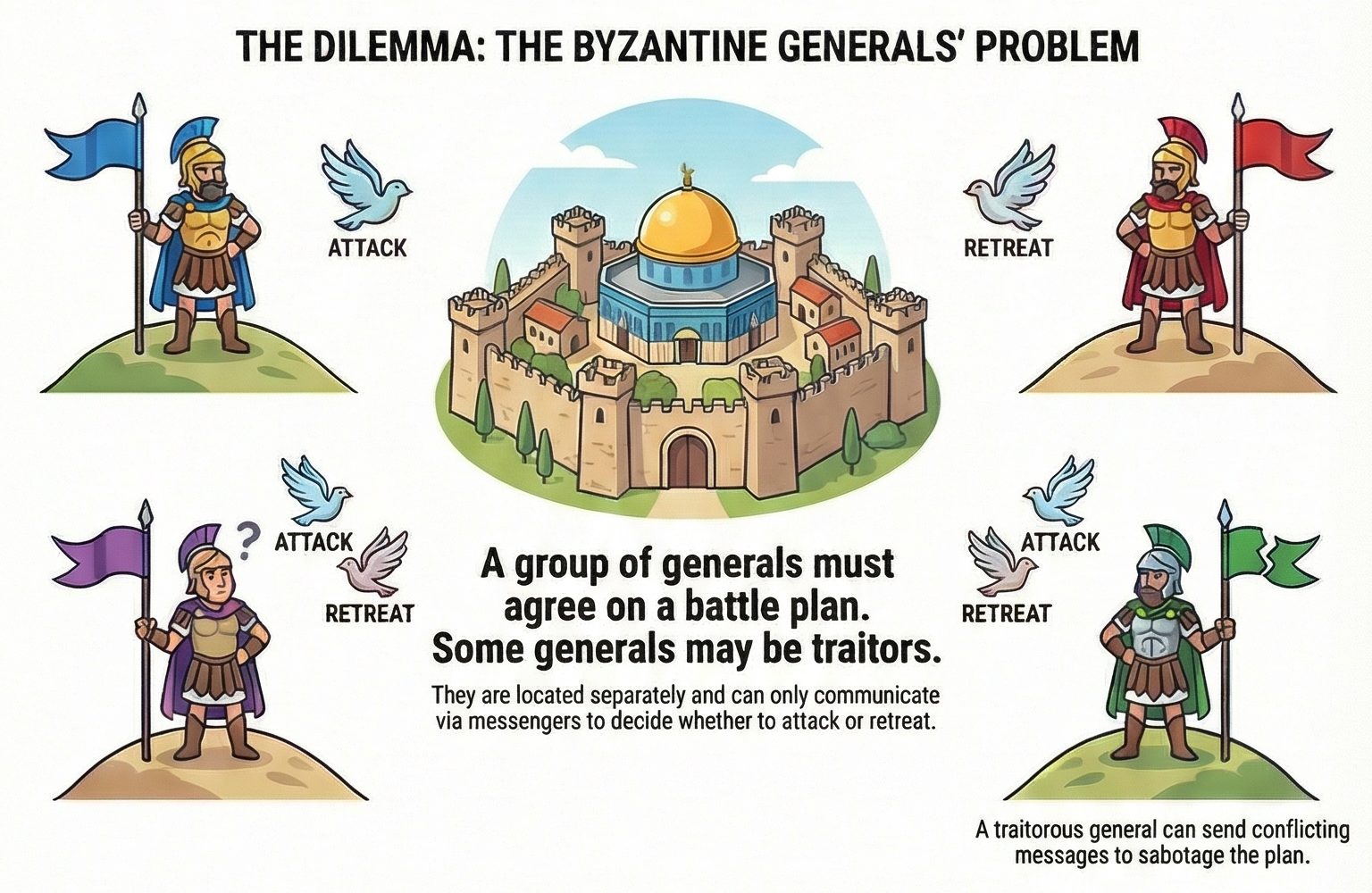

Imagine you're coordinating with colleagues across different offices to make a critical decision. You can only communicate via messages. Now imagine some of your colleagues might be actively trying to sabotage the decision by sending contradictory messages to different people. How do you ensure the honest participants can still reach agreement?

This is the essence of the Byzantine Generals' Problem.

1982: The Byzantine Generals' Problem

In their landmark 1982 paper, Lamport, Shostak, and Pease formalized this challenge through a vivid metaphor: Byzantine army generals surrounding an enemy city must collectively decide to either attack or retreat. They can only communicate via messengers, and some generals may be traitors.

A traitorous general might send an "ATTACK" message to one loyal general and a "RETREAT" message to another, attempting to sow discord and cause failure. The question: can the loyal generals reach consensus despite the traitors?

The Fundamental Impossibility

The paper proved a startling result that still governs distributed systems today: with oral messages, no solution can handle m traitors with fewer than 3m + 1 total generals.

Here's why these matters:

- With one potential traitor, you need at least four generals

- With only three generals, a single traitor can paralyze the loyal generals, making agreement impossible

- To overcome m traitors, you need at least 2m + 1 honest nodes to form a majority, plus m potentially malicious nodes—totaling 3m + 1 nodes

That extra honest node breaks the tie, creating the crucial honest majority. Without it, 2m honest nodes are paralyzed by doubt.

This wasn't just theory—it established the mathematical bedrock for all Byzantine Fault Tolerant (BFT) systems to come.

1999: PBFT Makes BFT Practical

For nearly two decades, Byzantine fault tolerance remained largely theoretical. Then came Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT), a landmark breakthrough that transformed BFT from an academic curiosity into a viable engineering solution.

PBFT was the first to provide Byzantine state machine replication that worked efficiently in asynchronous environments like the internet, without relying on synchronous timing assumptions for correctness. The performance breakthrough was remarkable: PBFT ran only 3% slower than standard unreplicated systems.

The Three-Phase Protocol

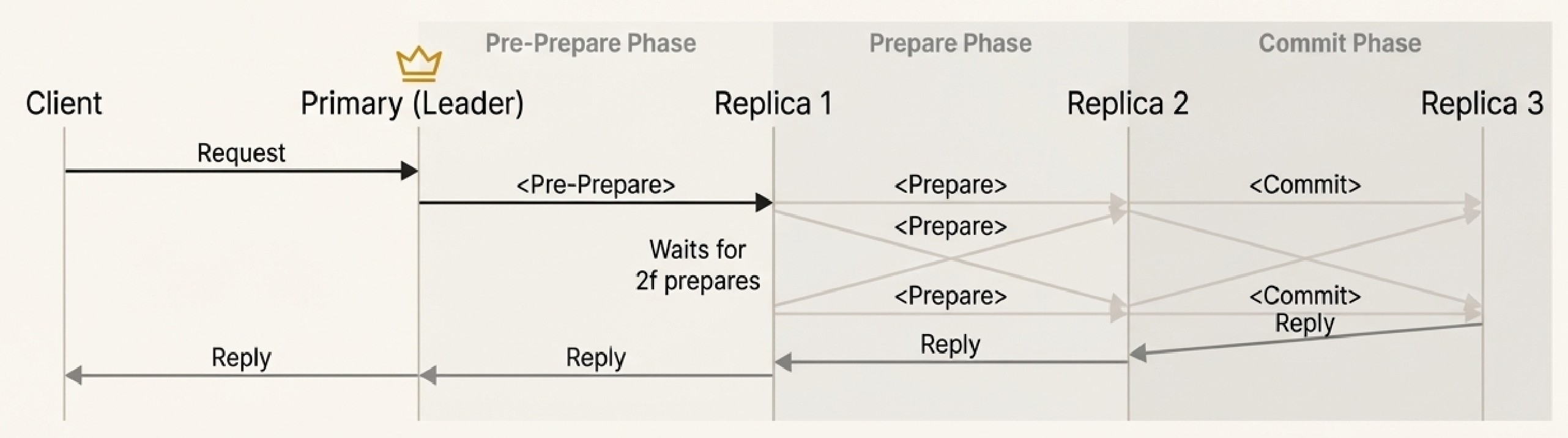

PBFT coordinates nodes through three phases to agree on the total order of requests:

- Pre-Prepare: The leader assigns a sequence number to a client request and broadcasts it

- Prepare: Replicas broadcast prepare messages, signaling agreement on the sequence number (nodes wait for 2f other prepare messages)

- Commit: Once nodes have seen enough prepare messages, they broadcast commit messages (after receiving 2f + 1 commits, the request executes)

The challenge? If the leader fails, the system must perform a complex view change to elect a new one. This process, while effective, incurs quadratic communication complexity—a bottleneck that would later drive innovation.

2016: Tendermint Simplifies for Blockchain

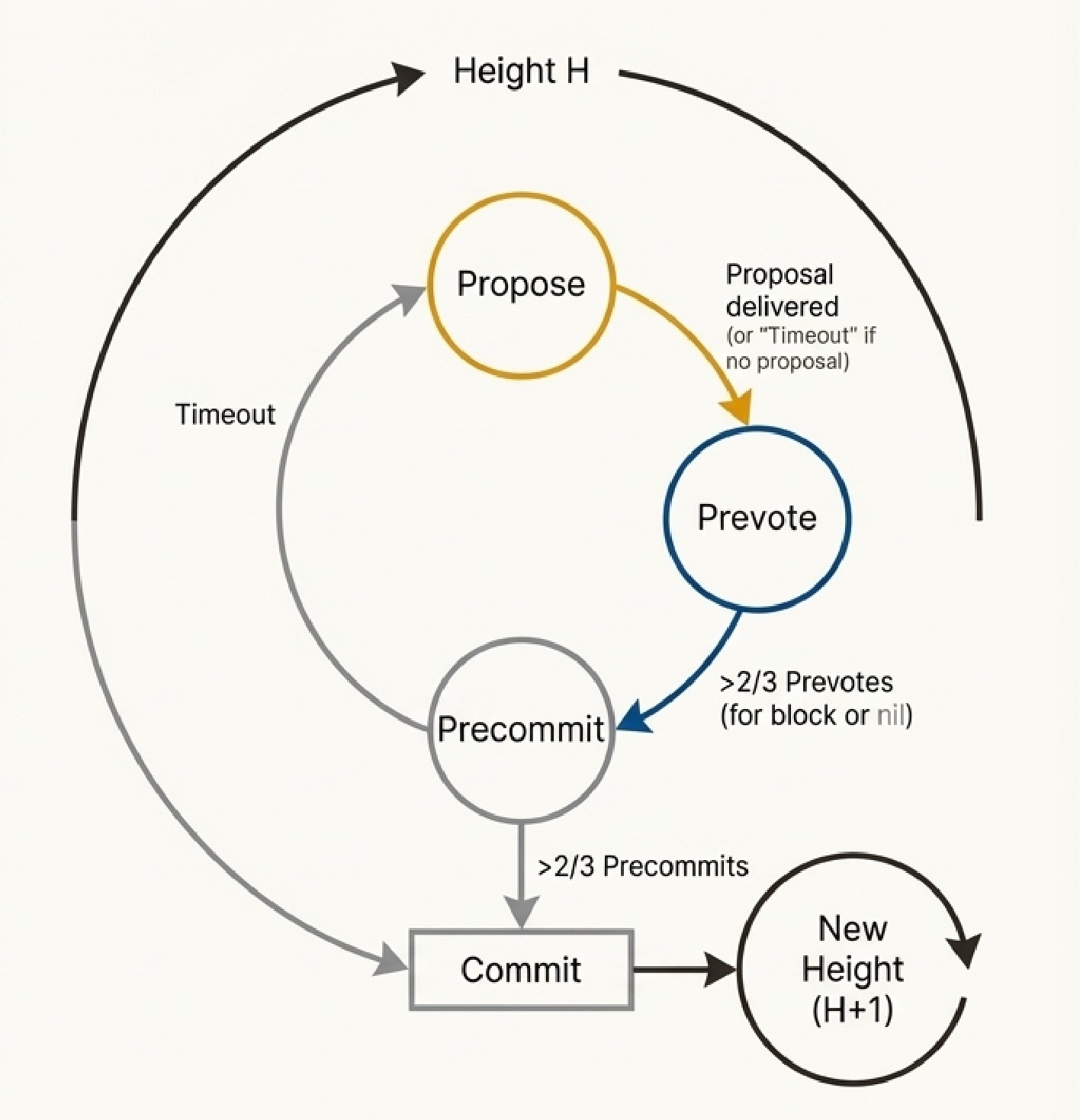

With the rise of blockchains, there was urgent demand for alternatives to energy-intensive Proof-of-Work. Tendermint was the first to popularize linking PBFT-style consensus to a Proof-of-Stake mechanism, where validators are chosen dynamically to produce blocks.

Tendermint's key innovation was radical simplification of leader replacement. Instead of PBFT's complex view-change sub-protocol, Tendermint uses a simple round-based state machine. If a leader fails, validators simply time out and move to the next round with a new, pre-determined proposer.

This simplicity and routine leader rotation made the protocol easier to implement and balanced communication loads. The trade-off? Tendermint lost responsiveness—latency depended on worst-case timeouts rather than actual network speed.

2018: HotStuff Achieves the Golden Standard

HotStuff emerged as a breakthrough that many consider the "golden standard for blockchains." It achieved three critical properties simultaneously:

- Optimistic Responsiveness: Latency depends on actual network speed, not worst-case timeouts

- Linear View-Change: Leader replacement has O(n) communication complexity instead of PBFT's O(n²)

- Simplicity: An elegant protocol that's easy to reason about

The Key Insight: Pipelining

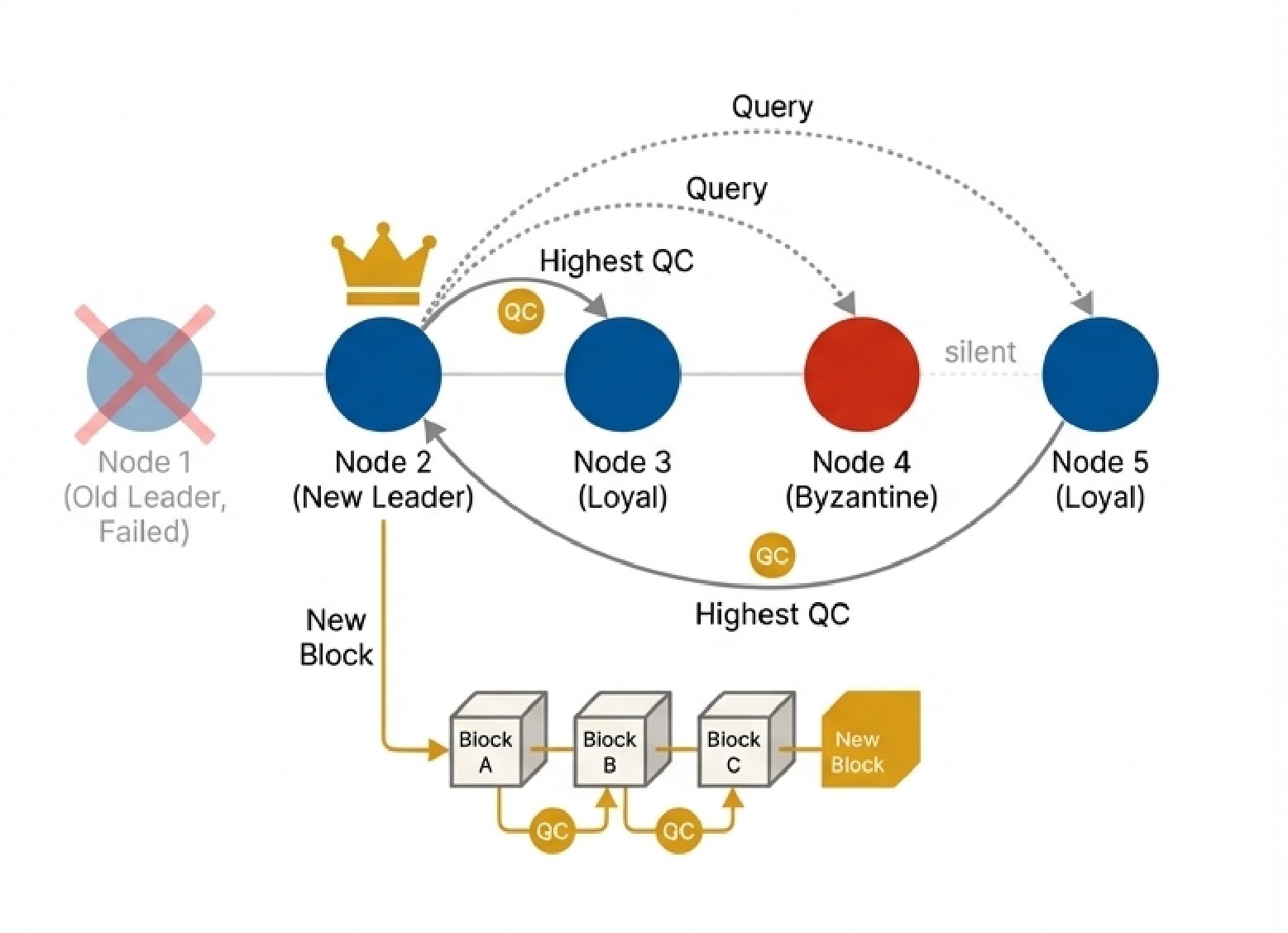

HotStuff's genius lies in pipelining. Its phases are structured identically, allowing them to cascade: a new block proposal serves as a vote for the previous block, creating a chain of certifications.

The three-chain commit rule elegantly ensures safety: a block is committed once it's at the head of a chain of three blocks, each proposed in consecutive views and certified with a Quorum Certificate (QC).

How does HotStuff achieve linear view changes? It uses an extra protocol phase to guarantee that if any node "locks" on a value, then a quorum of nodes (2f + 1) has received proof for that lock. This ensures the next leader will learn about the highest locked block by querying the network, even if f nodes are malicious.

2023: HotStuff-2 Reaches the Theoretical Optimum

While HotStuff was a major breakthrough, researchers noticed something: its three-phase commit was one phase more than the theoretical optimum of two. Could a protocol achieve all of HotStuff's properties with only two phases?

HotStuff-2 proved the answer is yes. This 2023 optimization reduces the protocol to an optimal two-phase commit, improving latency by as much as 33% without sacrificing linearity or responsiveness.

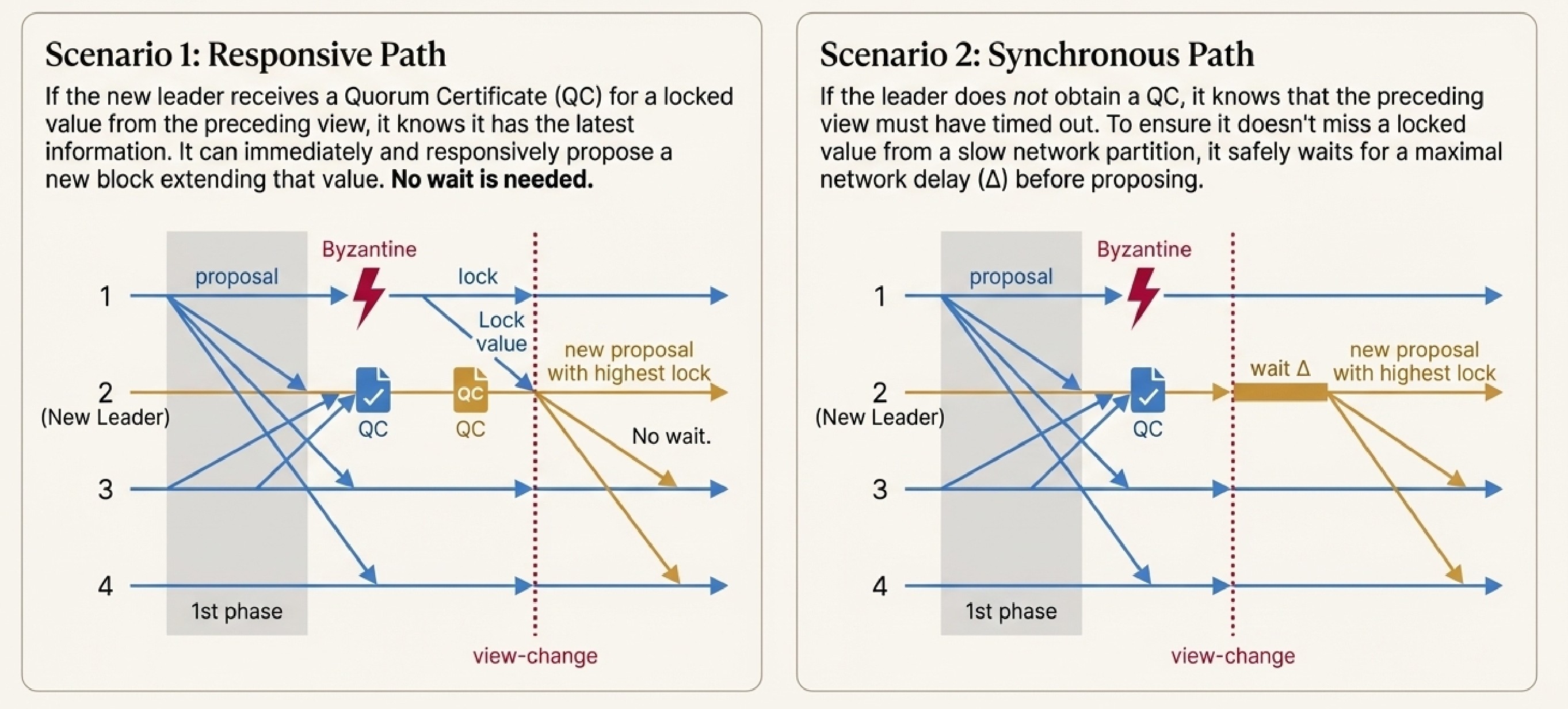

A Tale of Two Scenarios

HotStuff-2's elegance comes from adaptive behavior based on network conditions:

- Responsive Path: If the new leader receives a QC for a locked value from the preceding view, it knows it has the latest information and can immediately propose a new block—no waiting needed

- Synchronous Path: If the leader doesn't obtain a QC, it knows the preceding view timed out. To ensure it doesn't miss a locked value from a slow network partition, it safely waits for maximal network delay before proposing

This conditional logic achieves optimality while maintaining safety guarantees.

Epilogue

Understanding consensus is understanding how trust can emerge from mathematics and clever protocol design, even when participants have every reason to doubt each other. It's a testament to the power of distributed systems thinking—and a reminder that some of computing's hardest problems require decades of iterative innovation to solve.