How Reentrancy Exploits Drain Smart Contracts

How can a simple callback become a catastrophic vulnerability? In 2016, The DAO attack answered this question with brutal clarity: a recursive exploit drained $60 million in ETH, forcing Ethereum into a controversial hard fork. This wasn't the last time—from Uniswap's $25M loss in 2020 to Cream Finance's $18.8M exploit in 2021, reentrancy attacks have repeatedly proven that security is not a feature; it is the structure of your logic.

The Problem: Agreement in the Face of State Manipulation

Reentrancy is fundamentally a race condition. The vulnerability lies not in the code that runs, but in the code that awaits to run during state updates. When a smart contract controls to an external address before finalizing its state changes, that external code can recursively call back into the original contract, exploiting the temporal gap between execution and state commitment.

Think of it as a bank teller handing you cash before writing the withdrawal in the ledger. If you can ask for the cash again before the pen hits the paper, the bank is drained.

The Core Concept: The State Gap

At its heart, reentrancy exploits the temporal window between three critical phases: Execution Start (when an external call is made), The Attack Vector (the race condition window where the attacker can re-enter), and State Update (when the ledger is finally written). The vulnerability exists precisely in this gap—the moment between handing over control and committing the state change.

The Bank Teller Analogy:

Imagine a teller hands you cash (Interaction) before writing the withdrawal in the ledger (Effect). If you can ask for the cash again before the pen hits the paper, the bank is drained.

Technical Definition:

Reentrancy is a race condition where the vulnerability exists not in the executing code, but in the code that await() waits to run (the state update). The exploit occurs during the state gap when:

- Control is handed to an external contract (Interaction)

- That contract calls back before state changes are finalized

- The original contract operates on stale state

Anatomy of the Loop

Here's the vulnerable pattern that has cost the ecosystem hundreds of millions:

// Vulnerable Contract

function withdraw(uint amount) public {

require(balances[msg.sender] >= amount);

msg.sender.call{value: amount}(''); // [A] Control Handed Over

balances[msg.sender] -= amount; // [B] Executed Too Late

}

The Attack Sequence:

- Attacker calls

withdraw() - Victim sends ETH to attacker's contract

- Attacker's fallback triggers, calling

withdraw()again - Recursive calls continue while

balance > 0 - Victim updates balance only after recursion completes

This creates a destructive loop where each iteration drains funds before the ledger reflects the withdrawal.

Attack Patterns: Shared State Vectors

Reentrancy attacks can be categorized by how they exploit shared state within a contract. These "shared state vectors" represent the most common attack surfaces where a single contract's internal variables become the target.

Mono-Function Reentrancy

This is the simplest and most well-known form of reentrancy. The attacker exploits a single function by calling it recursively before the first invocation completes. Since the function's state update (like zeroing a balance) hasn't happened yet, each recursive call sees the original, unchanged state.

Why it works: The function sends ETH (or makes an external call) before updating its internal records. The attacker's receiving contract has a fallback() or receive() function that immediately calls withdraw() again.

function withdraw() {

// Attacker recursively calls this same function

// before it completes execution

}

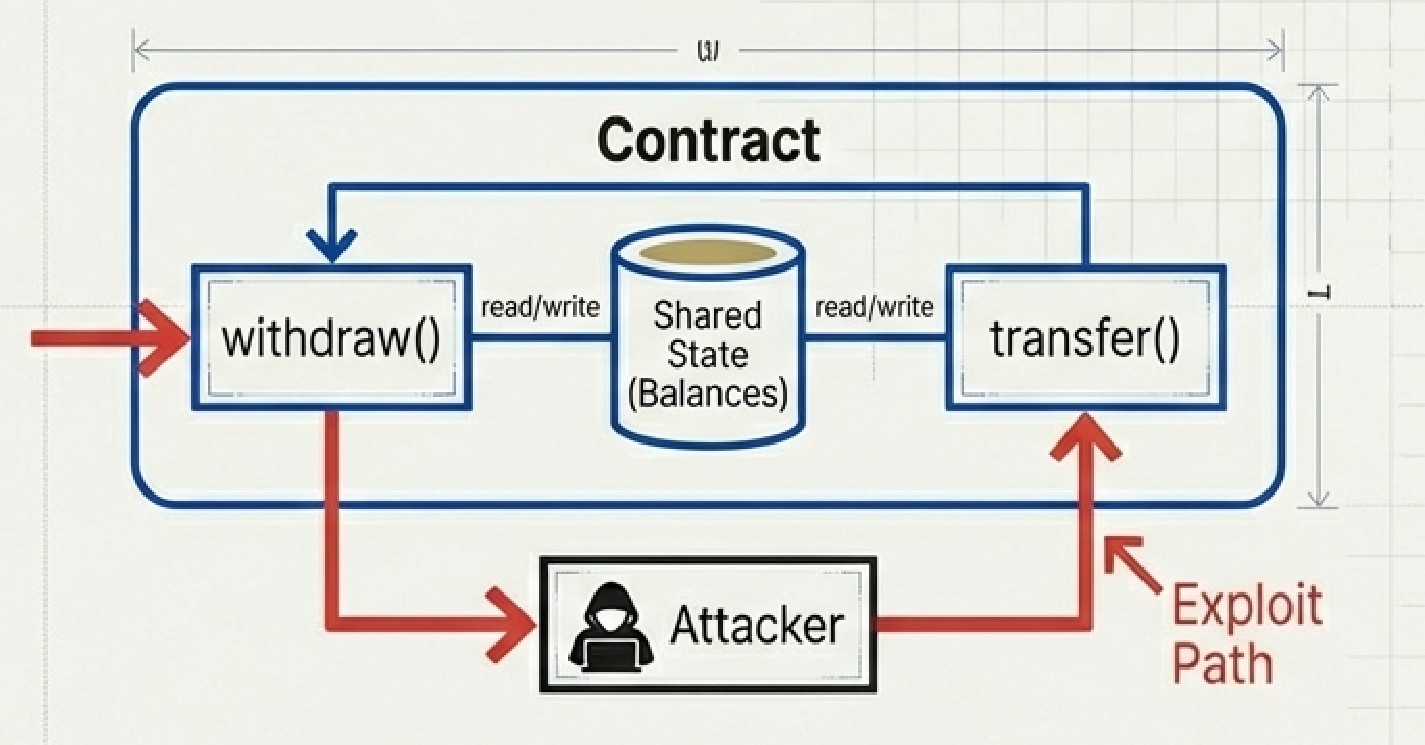

Cross-Function Reentrancy (The Side Door)

This is a more sophisticated attack where the attacker doesn't re-enter the same function—instead, they call a different function that shares the same state variables. Developers often add reentrancy protection to obvious functions like withdraw() but forget that other functions like transfer() can also manipulate the same balance.

While withdraw() is paused mid-execution waiting for the external call to complete, all other public functions remain callable. If any of those functions read or write the same state variables, the attacker can exploit the inconsistent state.

contract VulnerableContract {

mapping(address => uint) balances;

function withdraw() public {

uint amount = balances[msg.sender];

(bool success,) = msg.sender.call{value: amount}('');

balances[msg.sender] = 0;

}

function transfer(address to, uint amount) public {

// Shares the same balance variable!

require(balances[msg.sender] >= amount);

balances[to] += amount;

balances[msg.sender] -= amount;

}

}

Attack scenario: An attacker with 10 ETH balance calls withdraw(). Before the balance is zeroed, the attacker's fallback function calls transfer() to move those same 10 ETH to a collaborator address. Now the attacker has received 10 ETH and transferred 10 ETH—doubling their money.

Attack Patterns: Composability Threats

Modern DeFi protocols don't exist in isolation—they're composed of multiple interacting contracts. This composability creates new attack surfaces where reentrancy guards on individual contracts may be insufficient because the attack path spans multiple contract boundaries.

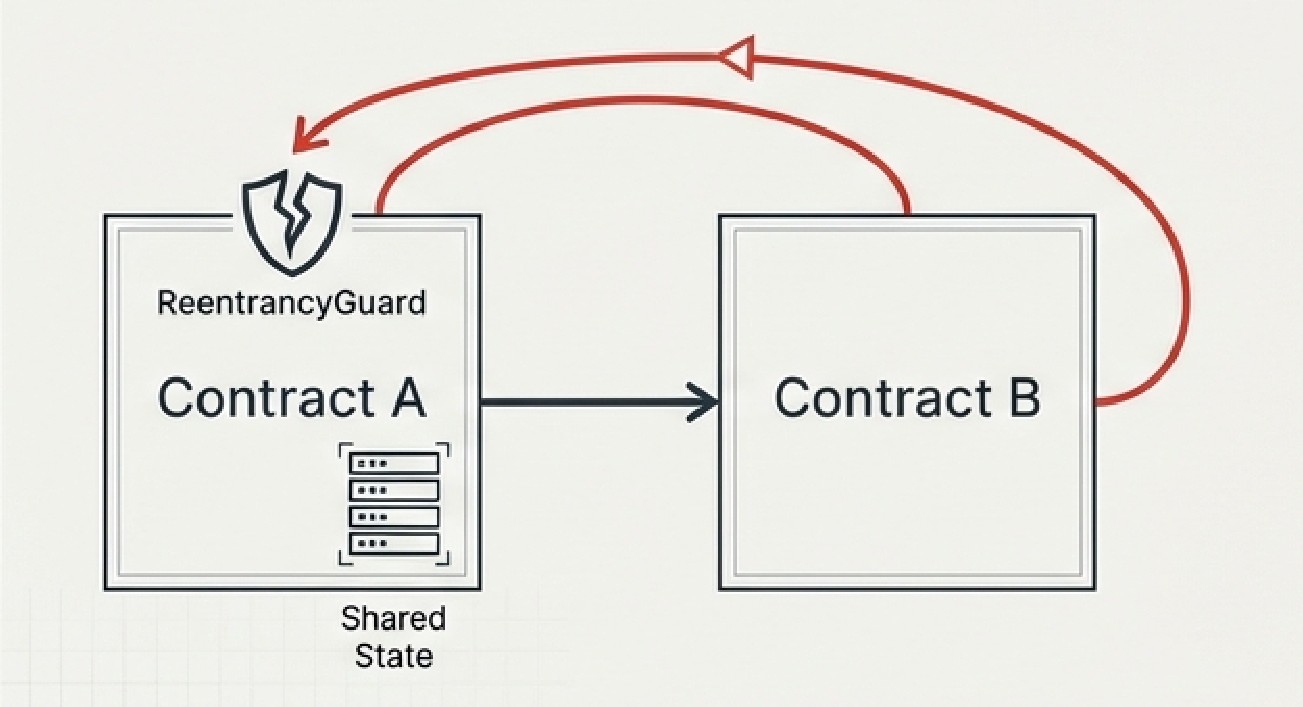

Cross-Contract Reentrancy

This attack exploits the relationship between two or more contracts that share state or have trust relationships. Even if Contract A has a perfect reentrancy guard, an attacker can bypass it by re-entering through Contract B—which may have access to modify the same shared state or call privileged functions on Contract A.

Real-world example: A vault contract (A) stores user deposits, while a strategy contract (B) invests those funds. Both contracts can update the vault's total balance. An attacker triggers a withdrawal from the vault, and during the external call, re-enters through the strategy contract to manipulate the balance calculation.

Why standard guards fail: OpenZeppelin's ReentrancyGuard uses a contract-local storage variable. If Contract B doesn't inherit from the same guard instance or check Contract A's lock status, the protection is bypassed entirely.

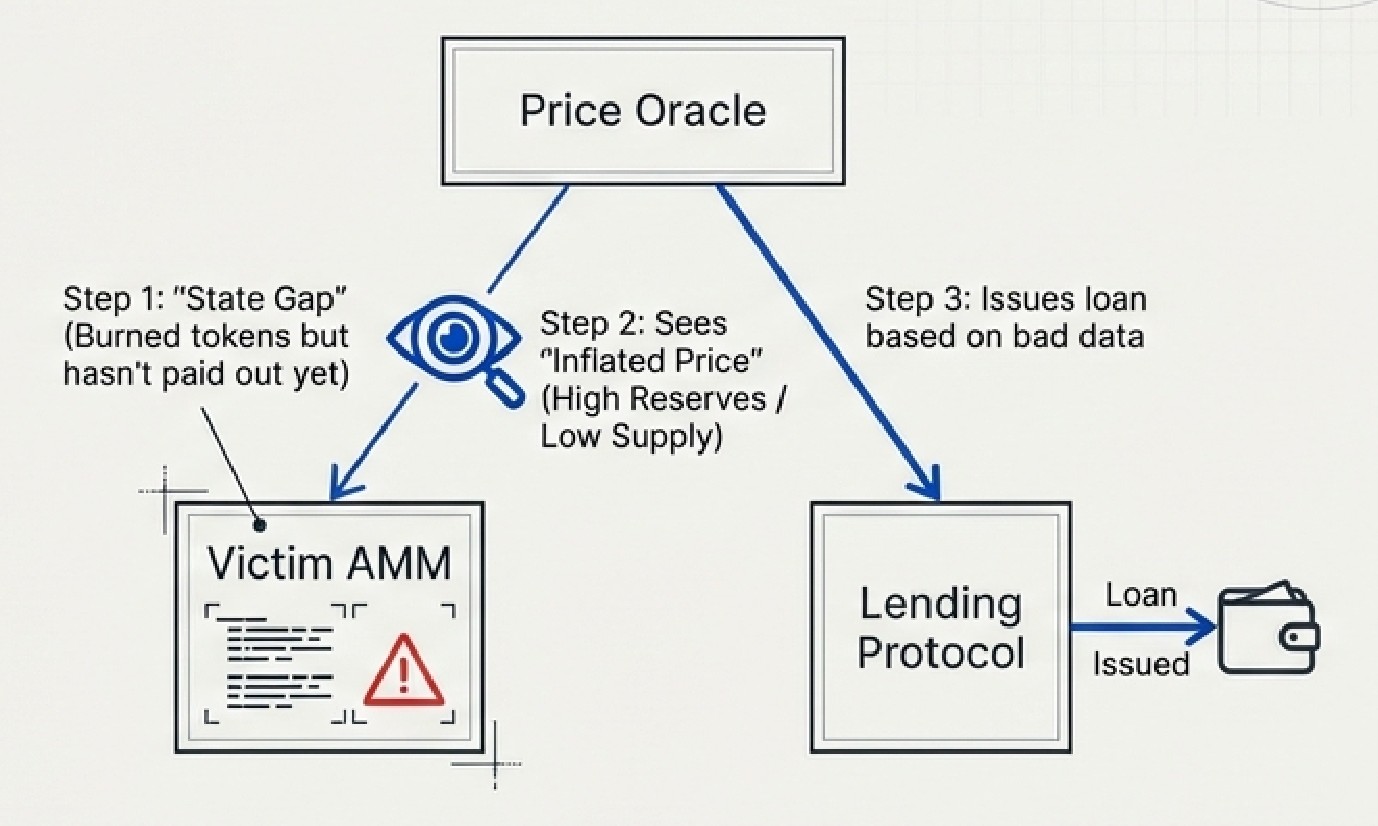

Read-Only Reentrancy (The Silent Killer)

This is the most insidious form of reentrancy because no state is modified during the attack—yet it still causes massive financial damage. The attacker exploits the fact that view functions can be called during the state gap, returning stale or manipulated data that other protocols trust and act upon.

How it works: During a legitimate operation (like removing liquidity from a pool), there's a moment when tokens have been burned but ETH hasn't been sent yet. At this instant, the pool's reserves appear artificially high relative to the token supply, inflating the perceived price. If a lending protocol queries this price during the callback, it will issue loans based on the manipulated valuation.

Why it's so dangerous:

- Traditional reentrancy guards don't help because no state is being written

- The victim isn't the contract being re-entered—it's a third-party protocol reading bad data

- Auditors often overlook view functions as "safe"

Notable victims: Curve Finance pools have been exploited multiple times through read-only reentrancy, where attackers manipulated get_virtual_price() during callbacks to trick lending protocols.

Defense Strategies

Now that we understand how reentrancy attacks work, let's explore the proven defense mechanisms. Each strategy addresses different aspects of the vulnerability, and in practice, you'll often combine multiple approaches for robust protection.

1. The CEI Pattern (Checks-Effects-Interactions)

The CEI pattern is the single most important defense against reentrancy. It's simple: always update your contract's state before making external calls.

The Three Steps:

- Checks – Validate conditions using require statements (happens first)

- Effects – Update all state variables (happens second)

- Interactions – Make external calls like transfers (happens last)

❌ Wrong Order (Vulnerable):

function withdraw(uint amount) public {

require(balances[msg.sender] >= amount); // Check

msg.sender.call{value: amount}(''); // Interaction ← TOO EARLY!

balances[msg.sender] -= amount; // Effect ← TOO LATE!

}

✅ Correct Order (Safe):

function withdraw(uint amount) public {

require(balances[msg.sender] >= amount); // Check

balances[msg.sender] -= amount; // Effect ← FIRST

msg.sender.call{value: amount}(''); // Interaction ← LAST

}

Why it works: When the attacker's callback tries to re-enter, the balance has already been set to zero. The require check fails, and the attack is blocked.

2. Reentrancy Guards (The Mutex Lock)

Sometimes CEI alone isn't enough—especially in complex functions with multiple external calls. A reentrancy guard acts as a mutex lock that prevents any function from being called while it's already executing.

How It Works:

modifier nonReentrant() {

require(_status != ENTERED, "ReentrancyGuard: reentrant call");

_status = ENTERED;

_;

_status = NOT_ENTERED;

}

The Execution Flow:

- Function is called → Lock is acquired (

_status = ENTERED) - Function executes → External calls happen

- If attacker tries to re-enter →

requirefails, transaction reverts - Function completes → Lock is released (

_status = NOT_ENTERED)

When to Use:

- Functions with multiple external calls

- Complex logic where CEI ordering is difficult

- As an additional safety layer alongside CEI

⚠️ Limitation: Standard guards use contract-local storage. They won't protect against cross-contract reentrancy unless both contracts share the same lock.

3. Gas-Efficient Guards with EIP-1153

Traditional reentrancy guards write to permanent storage (SSTORE), which costs ~20,000 gas per cold write. EIP-1153 introduced transient storage—data that exists only for the duration of a transaction.

Cost Comparison:

- SSTORE (Traditional): ~20,000 gas per cold write, persists forever

- TSTORE (EIP-1153): ~100 gas, persists only for the transaction duration

Why Transient Storage Makes Sense:

Reentrancy can only happen during a transaction. Once the transaction ends, there's no more attack surface. So why pay for permanent storage when you only need protection for a few milliseconds?

Implementation:

modifier nonReentrant() {

assembly {

if tload(SLOT) { revert(0, 0) }

tstore(SLOT, 1)

}

_;

assembly {

tstore(SLOT, 0)

}

}

This achieves 90%+ gas savings while providing identical protection.

4. Pull-Over-Push Pattern

Instead of pushing funds to users automatically, let users pull their funds when they're ready. This architectural change eliminates the callback vector entirely.

❌ Push Pattern (Risky):

The contract initiates transfers, giving recipients control during execution.

function distribute() public {

for (uint i = 0; i < users.length; i++) {

users[i].transfer(amount); // Each transfer is a potential attack vector

}

}

✅ Pull Pattern (Safe):

The contract records credits internally. Users claim funds separately.

mapping(address => uint) public credits;

// Step 1: Record the credit (no external call)

function recordReward(address user, uint amount) internal {

credits[user] += amount;

}

// Step 2: User claims their funds (isolated interaction)

function withdraw() public {

uint amount = credits[msg.sender];

credits[msg.sender] = 0;

payable(msg.sender).transfer(amount);

}

Benefits:

- No automatic callbacks during business logic

- Each withdrawal is isolated and follows CEI

- Failed withdrawals don't affect other users

5. Protecting View Functions

Read-only reentrancy exploits view functions that return stale data during a state gap. The solution: check if the contract is mid-execution before returning data.

The Problem:

Standard nonReentrant modifiers can't be used on view functions because they modify state (the lock variable).

The Solution:

Use a read-only check that examines the lock status without modifying it:

function getSharePrice() public view returns (uint) {

// Check if we're mid-transaction (lock is held)

if (_reentrancyGuardEntered()) {

revert("Reentrant call");

}

return totalAssets / totalShares;

}

When to Apply:

- Price oracle functions

- Balance calculation functions

- Any view function that external protocols depend on

Conclusion

Reentrancy attacks have cost the DeFi ecosystem hundreds of millions of dollars—from The DAO's $60M exploit in 2016 to Curve Finance's read-only reentrancy incidents in recent years. Yet these attacks are entirely preventable.

The key insight is simple: security is not a feature you add later—it's the structure of your logic from the start.

Your Defense Checklist:

- Always follow CEI – Update state before making external calls

- Use reentrancy guards – Add mutex locks to functions with external interactions

- Consider EIP-1153 – Cut gas costs by 90% with transient storage

- Prefer pull over push – Let users withdraw instead of pushing funds to them

- Protect your view functions – Check lock status before returning price data

- Assume all external contracts are hostile – Design with adversarial thinking

The recursion trap awaits those who ignore these patterns. But for developers who internalize them, reentrancy becomes a solved problem—not an existential threat.